For more than 30 years, the poster child of quantum computer algorithms has been a single algorithm that was always more proof of concept than truly useful application: factoring the very large prime numbers used in common cryptographic protocols.

Computer scientist Peter Shor’s subtle use of the way qubits can interact during a computation showed the fundamental power of the technique and how quantum computing can shortcut some parts of complexity theory. It also highlights how quantum and classical computing are interlinked.

The quantum Fourier transform (QFT) the algorithm employs looks for periodicity in the target number and then uses that to extract a set of best guesses that a digital computer can easily test to find the target prime numbers used to encrypt a piece of text.

Shor’s algorithm might prove profitable to some opportunists if “Q-Day” arrives well before enough critical applications have moved to safer, post-quantum cryptographic codes that are far less vulnerable to the factoring of large prime numbers. But it probably will not justify the billions invested so far and into the future, even if Bitcoin cannot migrate the underlying code for the currency before the unspent $75bn or so thought to be owned by the cryptocurrency’s inventor becomes vulnerable.

Other more long-term profitable opportunities may be available long before Q-Day sees a 2048bit RSA key broken: a task that calls for 6000 reliable qubits crunching through as many as 10 trillion operations. Focusing on Q-Day has taken much of the attention away from those potential applications.

Delivering practical advantages

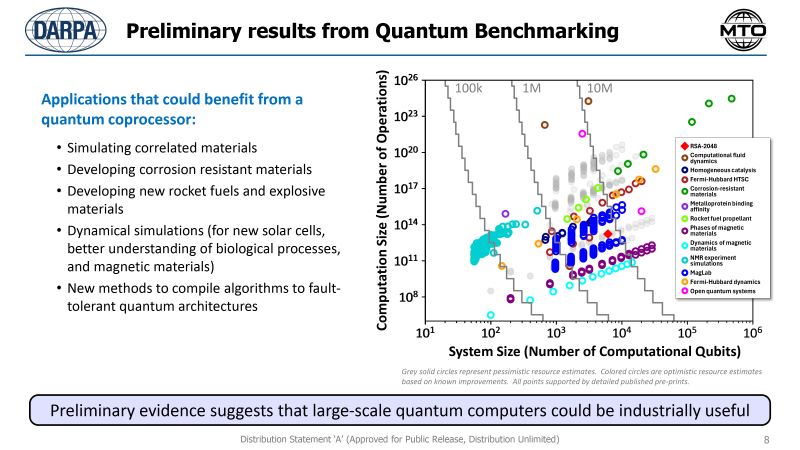

The question of whether quantum computing can deliver practical advantages has seen the US military-research agency DARPA create several projects to look at the issue.

Launching DARPA’s Quantum Benchmarking Initiative (QBI) in the autumn, programme director Joe Altepeter said, “There are a lot of physicists who have seen the past 25 years of hype and are convinced that even if you could build one of these, which [they believe] you definitely won't be able to do, it's never going to do anything more useful than you could do on your laptop.”

QBI researchers set out to determine if that is the case and, if it isn’t, what is the most likely architecture to be viable. A survey of applications and their potential speedup potential quickly winnowed the list of viable candidates from around 200 to just 10. The good news for quantum-computing research is that a high proportion of them do not need to wait for Q-Day. However, they also do not conform to the idea that quantum computing will be useful for many computer-science problems. At least, not for a long time.

The DARPA shortlist candidates are simulations of material properties that are themselves determined by quantum-level, sub-atomic behaviour. Magnetic properties look to be the lowest-hanging fruit, with some simulations coming into reach with just a few thousand qubits, if they are reliable qubits.

Altepeter notes that most of the applications on the DARPA shortlist will need the kind of fault-tolerant architecture that a Q-Day machine would implement. It will not be enough to rely on the noisy, error-prone qubit handling that today’s experiments can deliver.

That places a strong emphasis on efficient quantum error correction codes and the hardware redundancy they imply.

Much of the existing work on error correction derives from another of Shor’s fundamental contributions to the field. These codes act as parity checks that, through a set of auxiliary qubits arranged artfully to prevent the quantum entanglement from collapsing when the circuit analyses a temporary state to correct it.

The downside is that in a superconductor machine it can take 20 or more qubits to realise a fault-tolerant virtual qubit and only for short periods of time. Ion-based machines fare better, but these may not scale as well as their superconducting counterparts.

Photonic machines look to have scaling on their side but face challenges supporting the all the gates needed to make a full quantum computer. However, a hybrid photonic-silicon architecture developed by PsiQuantum was, alongside a superconductor-based design from Microsoft, the first to be selected in the next phase of DARPA’s hardware-benchmarking programme.

Above: Manufacturing PsiQuantum's silicon-photonics wafers

Variational quantum algorithms

Variational quantum algorithms (VQA) do not appear on the DARPA shortlist but may act as a way of using today’s quantum architectures in useful applications. They represent a step beyond a class of machine already in use, albeit not widely. This the quantum annealer, exemplified by the hardware made by D-Wave Systems, and ironically one of the companies that saw its stock price plummet after Nvidia chief Jensen Huang’s speech at the Consumer Electronics Show poured cold water on the idea Q-Day would arrive anytime soon.

However, experience with algorithms designed for these systems also demonstrates that quantum-inspired digital programs may be just as useful as those that run on quantum hardware.

In principle, quantum processes like entanglement are good for handling optimisation problems. The idea is that you encode a series of qubits into a Hamiltonian and then attempt to reduce its overall energy to get an answer that is difficult to compute on a conventional computer.

The most obvious example of this is the Travelling Salesman Problem, where the aim is to compute the shortest route between a list of destinations. Unfortunately, operations in quantum-annealing and similar “Ising machines” modelled that use real or simulated magnetic spin interactions are quite slow because the process relies on tiny changes in energy at each step. Conventional electronic machines modelled on the same optimisation processes that run on custom digital hardware or graphics processors can wind up delivering results more quickly, though they may use more energy to get to an answer.

In an analysis performed a couple of years ago of how well quantum annealing could work in coordinating cellular base stations to handle the enormous complexity of multiple antenna transmission schemes, researchers from Princeton University and University College London estimated that it might take until the mid-2030s before quantum annealers demonstrate enough performance and power efficiency to take over from purely digital simulations.

However, in VQA systems, quantum annealers work alongside simple quantum-gate circuits in a design that may provide a more obvious boost to performance compared with purely digital machines.

The annealing part of the system guesses an initial state and the system cycles through circuit updates until it reaches what seems to be the optimum state.

Classical hybrids

As with quantum annealing, classical hybrids may prove an important direction for further work. Goethe University Frankfurt researcher Manpreet Singh Jattana showed last year how a combination of a D-Wave machine, IBM’s existing quantum machines and a conventional computer could combine to iterate more quickly through problems like graph colouring and physics simulations.

Hybrids of quantum and conventional computing may appear in another way.

Peter Barrett, general partner at venture-capital firm Playground Global, argued in MIT’s Technology Review that smaller-scale quantum simulations could help train machine-learning models to predict material interactions.

In principle, the quantum machines would deliver more useful data to these models because they should be more accurate than the density functional theory algorithms that digital computers can run, and which turned out to give the wrong answers for modelling novel superconductors such as the LK-99 material discovered in 2023.

As the AI models should run far faster than quantum simulations, they could refine a list of candidate materials of molecules for a particular task, with supercomputers or quantum computers reserved for checking the shortlist.

Similar hybrids may prove to be the template for taking quantum into the mainstream, without demanding the huge hardware investment needed for the Q-Day machine.