Back in October, the Centre for Process Innovation (CPI), a UK-based technology innovation centre and part of the High Value Manufacturing Catapult, announced that it would be working with Pireta Technology to scale-up wearable technology in textiles.

Pireta Technology has expertise in the printed electronics sector and is able to coat individual fibres of fabrics with metal, creating selective patterns to form a printed circuit board and does this without changing the fabric’s physical and mechanical properties.

By working with CPI, and using its state-of-the-art equipment, Pireta is looking to reduce existing manufacturing timescales while optimising the resolution of the electrode pattern.

"Our aim is to demonstrate the commercial viability of our technology," explains the company’s Chief Commercial Officer, Ian Russell.

Pireta Technology was set up by CEO Chris Hunt while he worked at the National Physical Laboratory, where he headed up a multidisciplinary team of scientists looking at material problems in electronics interconnects.

"NPL were keen to commercially exploit inventions developed in its laboratories – and Pireta was spun out in 2017," says Russell.

Wearable electronics, in its broadest sense, can include devices like Fit-Bits and Apple watches but, according to analysts, it’s going to be textile-based wearables that will have the biggest impact on this fast-growing market.

"It’s the technology around adding conductivity to textiles, where we’re seeing the real growth, and that’s where Pireta is focused," Russell says.

Wearable technology is seen as being an intrinsic part of the Internet of Things and will allow devices embedded in fabrics to send and receive data via an internet connection.

Pireta’s technology has the potential to unlock many of the current restrictions associated with smart textiles.

"Enabling this technology will impact significantly on smart textiles and wearable electronics, especially when there is an increased demand in this area from multiple industries," says Russell.

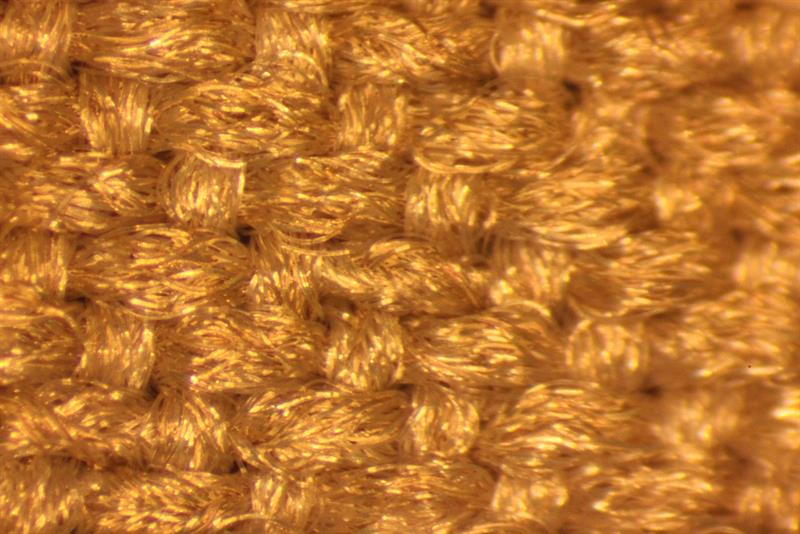

Close up of the coated fabric

Close up of the coated fabric

"The opportunities for textile wearables are huge. We’re talking primarily about wearable medical devices, but other opportunities exist in terms of tracking an individual’s psychological parameters in military applications or the emergency services, for example. They can also be used in elite sports to measure stress levels."

Patent pending technology

Pireta has come up with a patent pending technology that, according to Russell, "has the potential to enable truly wearable smart electronic systems, and we’ve achieved this through the attachment of copper to the fibres of textile yarns."

The technical issues associated with wearable fabrics are formidable. "At present conductivity can be added to a material in a number of ways each, however, has its own drawbacks," according to Russell.

"You can add conductivity via a metal coating to a fabric, but that makes it difficult to create a pattern so it’s not really suitable for a printed circuit.

"Another method is using printed inks, but while they can be used to create a pattern, the TPU plastics used as a base layer can impact the handling, drape and feel of the material – the stretch and breathability of material can also be affected – that’s critical if you’re deploying sensors and need them to be in close contact with the body.

"Another technology is conductive threads where a thread can be coated with a conductive metal – while this is ok it tends not to be a scalable process and it’s awkward to connect the yarn to a component. Soldering doesn’t work, and while forms of stitching and the use of certain adhesives is possible, neither are robust."

According to Russell, all these technologies are problematic and for wearable fabrics to be accepted, they need to be not only wearable but durable with the ability to stretch and breath and be washable over the longer term.

The technology devised by Pireta enables wearable electronics to be more discrete as the electrodes are actually integrated into the fabric, retaining its characteristics - the way it feels and hangs - and can be applied to knitted, woven and non-woven, natural and synthetic textiles.

"Our technology enables real ‘wearable’ technology," Russell says, "with discrete devices disappearing and being built into the clothes we wear. It allows for complex designs and patterning via a simple printing process."

That process involves five-stages and employs proven aqueous processes and commercially available chemistries, Russell explains.

"The fabric has some pre-conditioning, but the chemistry is relatively straight-forward. After that we look to activate the textile and functionalise it. This is the key part of the process and involves using a jet ink printer to coat individual fibres with a nano-metal in ionic form. The process

bonds the metal to the individual fibres in the yarns. The process is fundamentally the same, whichever textile is being used.

Once the catalyst is down we then look to optimise its functionality by increasing the thickness of the metal coating. After that we use an immersion process using silver or an organic passivate to stop oxidising and provide isolation."

RF transmission line

RF transmission line

According to Russell, the process gives the textiles a low sheet resistance, creates a conductor that does not crack, and a fabric with the flexibility, breathability and performance that can be maintained even when its washed or stretched.

"We’re providing the function of the printed circuit board on a textile with interconnection between components. Not only that but you can also implement other devices such as sensors, antennas or energy harvesting devices simply by printing conductive patterns – the main thing is that our technology permits interconnectivity between components that can now be mounted onto textiles.

"Think of it as a form of structural electronics, where the textile becomes the substrate on which the circuit is built and assembled.

"The process that we have developed is well characterised and understood, but while we can prototype and undertake small volume production, we’re not at the stage where this is fully set up to go into production," Russell concedes.

"That’s why we are working with CPI. We’re looking to go from bench top production and scale to the point where this process could be operated on a roll-to-roll process."

- Ian Russell is Chief Commercial Officer, at Pireta. He has over 20 years of experience managing early-stage business ventures working in high-technology sectors, Ian Russell has built and managed international development, sales and service organisations. He has negotiated multi-million dollar technology licensing contracts and strategic alliances with key vendors and partners and led three successful trade sales of early-stage technology-based businesses to publicly listed companies.